- Home

- James Goodson

Tumult in the Clouds Page 2

Tumult in the Clouds Read online

Page 2

‘OK. We’ll share it. That way we’ll keep each other warm!’ and she snuggled into my arms as I wrapped the blanket around us.

‘What happened to the rest of your clothes?’ I asked.

‘We were dressing for dinner when the torpedo struck. We grabbed what we could and ran.’

I looked around and saw we were surrounded by young girls in various stages of undress. Some had borrowed sweaters and jackets from members of the crew. Others were huddled in blankets. At least most of them had life-jackets. As they snuggled together around us, I showed my surprise.

‘Who are you?’

The little brunette laughed. ‘We’re college kids. We’ve been touring Europe after graduation. I guess our timing could have been better. I’m Jenny. This is Kay. That’s Dodie.’

They were a wonderful, cheery bunch, cracking jokes and singing songs. We were an oasis of fun in the lifeboat. Most of the others were frightened or seasick or both. Many were refugees, mostly from Poland. Many were Jewish, but by no means all.

I was surprised at how large the boat seemed, even as it rolled and pitched on the North Atlantic swells. Up in the bow was a member of the ship’s crew, and another in the stern. In spite of the crowd in the boat, they had been able to get some of the oars out, and had got some of the men to start rowing. After getting warmed up, I felt guilty at not pulling my weight. I got up and picked my way carefully to within shouting distance of the seaman in the stern.

‘Do you want me to help out on the oars?’

He was surprised to find a volunteer. ‘Ay! These two here are having a struggle. Maybe you could help them out. All we need to do is to keep away from the Athenia and head into the waves.’

I took the place of a young Jewish boy who was more of a hindrance than a help to his partner on the oar. He didn’t speak English, but was delighted to find I spoke German, which meant he could communicate with me in Yiddish. He was even happier to be relieved of his task. The other man on the oar was also young. He didn’t speak Yiddish or German, but he spoke a little English. He seemed to be somewhat handicapped by something hanging out of his mouth. At first I thought it was saliva or spittle, but when he saw me looking at it, he took it out of his mouth, and I saw that it was a St Christopher medallion on a silver chain around his neck.

‘He save us!’ he said and put the medal back in his mouth, clamped between his teeth.

I nodded, but I sincerely hoped that St Christopher was being helped by the last messages of the Athenia’s wireless operator. I knew that the crack of the second explosion had been a shell from the U-Boat, but I had seen that although it had killed a few people on the upper deck, it hadn’t hit the radio mast or super-structure.

After an hour or so on the oars I suggested that we could stop rowing. We were far enough from the ship to be out of danger, but shouldn’t get too far from her, because the rescue ships would be heading for her last reported position.

I went back to Jenny and my friendly college girls. Through the night, we clung together, chatted, sang and slept fitfully. At one point, I remember the Jews joining in singing that beautiful plaintiff dirge which became the hymn of the Jewish refugees, oppressed, and martyred throughout the world.

Occasionally we looked across to the stricken Athenia. We were amazed at how long she was staying afloat. She was sinking lower in the water, and listing further, but during most of the night, she was still there. It was about 1.30 a.m. when everyone in our boat woke out of their fitful sleep and looked across at the dark hulk. There had probably been a noise of some kind; or perhaps a shift in her position, although I don’t remember either. Anyway, we were all watching when the stern began to sink lower. Soon it seemed to me that most of the near half of the ship was under water. Everything was in slow motion. Gradually, as the stern disappeared, the bow began to rise. We could see the water cascading off as the great ship reared up; slowly, and with enormous dignity. It was frightening, unbelievable, awesome. Finally the entire forward half of the ship was towering above us. When it was absolutely vertical, it paused. Then she started her final dive; imperceptibly at first, but gaining in momentum until she plunged to her death. A column of water came up as she disappeared, then there was only a great turbulence, and then nothing but the rolling sea and some floating debris. We felt lonelier and sadder. There was no singing now. We were tired and shivering with cold.

It was 4.30 when I saw it looming up through the dark. It was a ship. It was even carrying lights. We were too numbed to cheer. There was just a stirring in the boat; a grateful murmuring. The rowers picked up their oars and started rowing slowly towards the ship.

Other lifeboats were doing the same. Soon we found ourselves close to the big rescue ship, surrounded by five or six other boats. The big ship had stopped as soon as she was close to the boats. Rope ladders were dropped over the side near the stern of the ship. She was a tanker and must have been empty. She towered above us and we could see the blades of her big propeller as we came around to her stern. I looked up and saw her name and home port: ‘Knute Nelson – CHRISTIANSAND’; a Norwegian tanker.

As we came close, I called on the seaman on the tiller of our boat to keep us away from the menacing propeller. It was not moving, but I knew it could windmill, or the Captain might call for some weigh, unaware of the boats under his stern. One life-boat was being tossed by the waves ever closer to the propeller. I yelled across to them, but apparently there were not enough rowers to stop the drift. Then the great propeller started to turn, churning up the water, and sucking the lifeboat in under the stern. As we watched, they were drawn into the whirlpool. We saw one big propeller blade slash through the boat; but as the shattered bow went down, the rest of the boat was lifted by the next blade coming up. The rearing, shattered boat spilled its human cargo into the churning water.

I called to the man on our tiller and on the rowers to make for the spot where the survivors were floundering in the water. The screw was no longer turning, and the ship had moved forward slightly. Some of the strong swimmers were already making for the bottom of the rope and wooden ladder dangling down the side of the ship close to the stern; some were pulled into our boat; others clung to the gunwales or oars for the short distance to the ladder; but many just disappeared under the foaming water.

We got the survivors from the broken lifeboat onto the ladder first. Then it was the turn of the weakest from our own boat. It wasn’t easy. The boat was rising and falling on the waves, smashing against the steel sides of the tanker. Sometimes we got someone onto the ladder only to have them fall back into the boat as the ladder swung, or the boat dropped away too soon. We had to get them to get onto the ladder when the boat was at the top of its rise.

Finally there was no one left in the boat but the two seamen, the American college girls and myself. One by one, the girls started up the twisting, writhing ladder. Even for lithe, young, athletic teenagers, clambering up the tricky rope ladder took all their strength and concentration. There was no way they could keep the blankets wrapped around them; even those who had huddled into seamen’s jackets which were far too big for them, wriggled out of them before attempting to scale the towering side of the tanker.

When I finally reached the top of the ladder and was hauled over the rail by two large Norwegian sailors onto the deck. I saw the incredulous Captain of the Knute Nelson staring at a group of shivering girls, mostly dressed in pants and bras, and nothing else. He hurried them to a companionway.

‘Go down! Down! Any door! Any room! Warm! You must have warm!’

I followed them down the iron stairs until we came to a lower deck, and into the first door. The cabin was dark, but warm! It smelt cosily of human sleep; there was the sound of heavy breathing.

The light came on. We saw a series of bunks, one above the other. In each bunk was a large Norwegian seaman. The girls had only one thing in mind: to get warm. They didn’t hesitate. The seamen, who had been at sea for weeks, and didn’t even know that war had

been declared, awoke to find half-naked girls clambering into their bunks and snuggling up to their warm bodies under the rough blankets. I’ll never forget the expressions on the faces of those big Norwegians. They knew they must be dreaming.

When we had explained what had happened to those who understood English, and they had translated it to the others, those magnificent gentle giants turned out of their bunks, made us coffee, served out hard-tack biscuits, lent us their sweaters, and blankets, showed us the way to the ‘head’, and made us feel that, in spite of what we had been through, life was good!

We slept the sleep of the exhausted for many hours. When we came to, we learned that, as a ship of a neutral country, the Knute Nelson was taking us to the nearest neutral port: Galway on the west coast of Eire. We heard that other rescue ships, including British destroyers, had picked up other survivors.

Yes, Ireland is as green as they say, and Galway is as Irish as it’s possible to be. We saw the green of the fields from the deck of the Knute Nelson as we sailed into Galway Bay. We saw Galway when we glided up to the docks. The whole city must have been there. We said our fond goodbyes to our Norwegian Captain and his crew. They insisted that the girls keep the voluminous sweaters which reached to their knees, and were rewarded by enthusiastic kisses of gratitude. I thanked every member of the crew. For me they joined that long list of great Norwegians, a list out of all proportion to the size of the country. They were also the first of a long list of solid Norwegian friends who seemed to turn up when I needed help; Berndt Balchen, Harald Swenson, Brynyulf Evenson, Arne and Bengt Ramstad and many others. A very special people, the Norwegians.

But on the docks of Galway, a more tumultuous welcome was waiting for us. Galway was a centre of republicanism in the neutral Republic of Eire, and one would expect the citizens to be neutral or even anti-British, but there was nothing neutral about the weeping, cheering Galway crowd on that September day in 1939. They swamped us with their sympathy and generosity. They listened to every harrowing story, and hung on every word. They tried to unite husbands and wives, and help children find their parents, and they cried with them when hope gradually faded.

As we arrived on the quay, those survivors who had been brought to Galway by the British destroyers, besieged us to ask if we had seen or heard of the friends and relations from whom they had been separated. Many were desperate and gave way to their grief and anguish. Others just asked with a terrible quiet dignity. I remember a brother and sister about ten or twelve years old who asked in clear treble voices if we had seen their parents.

For the first time, I felt an overwhelming fury that was to sweep over me time and time again during the war. No one had the right to cause such suffering to innocent people. At first my rage was against the Germans, but later, when I saw the same suffering among their innocents, my fury was against those who used their power with such callous lack of responsibility to heap personal tragedy on the little people who wanted only to live; to cut down the young before they have had time to savour life; to deprive the old of the peace and fulfilment of age for which they had toiled throughout their lives; to tear away from parents the sons and daughters without whom life has no meaning; to inflict on a young woman the loss of a husband and condemn her to a life of loneliness and mourning; to sentence to cruel death those who are killed; to sentence to a crueller life those who are bereaved. No one had the right to cause such suffering, and those who assumed that right had to be stopped and punished. That was the vow; simple and profound; corny and devout. That was the way we were; no doubts; we knew what was right and wrong, and we knew what we had to do.

Meanwhile we were swept up by the Irish of Galway, who literally gave us the clothes off their backs. I remember being overwhelmed by sympathetic citizens who almost carried me off to a nearby pub. I was dressed only in slacks and a shirt. As we went into the bar, one of the crowd selected a raincoat from those hanging from pegs in the entrance and insisted on putting it on me.

‘But is this yours?’ I protested.

‘Of course not! It’s yours! Fits you to a tee!’

‘But it belongs to someone!’

‘Sure, he’d want you to have it!’ The others agreed, and slapped a cloth cap on my head to complete the outfit.

The emotional reception was not reserved for the Canadians and Americans, but was just as warm for the English. Among the sympathetic crowd in the pub were a number of Irishmen wearing in their lapel a simple gold circlet. When I asked what it was, they explained that they were members of a movement devoted to the promotion of everything Irish, and opposed to everything English. The gold ring emblem meant that they had made a vow to speak only Irish and never speak English.

‘But you’re not speaking Irish now,’ I said.

‘Well, we have to learn it first! That’s why we’re here in Galway.’

It wasn’t easy, but I finally slipped away from my exuberant friends. The other survivors were being allocated to various hotels or billets. By the time I arrived, there wasn’t much left. In any case, as a third class passenger with no cash, and no hope of getting any, I wasn’t expecting much.

As I waited patiently, I recognised one of the girls from our lifeboat, and joined her. She was a striking girl, as tall as I, with golden blonde hair and a magnificent athletic figure.

‘Remember me? We spent last night together.’

‘Of course, but I don’t remember your name.’

‘Jim Goodson. What’s yours?’

‘Katerina Versveldt, – but wait a minute, I think they were looking for you. I think that was the name they called out on the loudspeaker.’

We went up to the survivors’ centre, and, sure enough, to my surprise, it was my name that had been called. Even more amazing, a well-dressed businessman came up and greeted me with obvious enthusiasm and a welcoming smile.

‘Mr Goodson, I’m Jack Warren. Thank God you’re safe! We’ve got a room ready for you in our home, and you can stay as long as you like!’

‘That’s very nice of you, but I don’t understand. How did you know about me?’

‘Your uncle knew you were on the Athenia, and that most of the survivors were being brought to Galway. He got in touch with his friend Joe Boyle who’s with Shell Oil, and they got in touch with me. I’m the Shell manager here.’

‘Well, I can’t imagine why Shell should go to all this trouble just for me; and I’m afraid I’ll be imposing on you.’

‘Nonsense, this is the least we can do. And how about your friend? Can we put you up too? Let’s go!’

The Warrens opened their house and their hearts to us. They used their precious petrol to take us through the West Irish countryside. They showed us the wild rocky coast, the little fields surrounded by low stone walls of stones fitted together with no cement or mortar. They explained how many of these minute plots had been hewn out of the solid rock. First the rock had to be cracked by building a fire on it and then dousing it with cold water. Then a wedge of wood was pounded into the crack, and water poured over it to make it expand, thus extending the cracking process. Then followed the laborious process of pounding and prising, until the cracked pieces of rock could be lifted out and piled around the plot. Finally, baskets of seaweed, kelp, and what earth could be found were carried to the cavity, and, after years of care, there was a little plot capable of producing potatoes, or enough grazing for a cow or goat.

The Warrens lived between Galway and Connemara, where they showed us the Claddach, the old section, where the little white, thatched cottages had stood unchanged for over a century. They had wooden doors split across the middle like a stable, so that the top half could be opened to let in the light and air, while the bottom half stayed closed. Most of them had dirt or stone floors, and the chickens wandered in and out at will.

But we only had two days on peaceful Galway Bay. We were to be sent from neutral Ireland to Glasgow, presumably to be given passage from there back to Canada or The States.

The night fer

ry from Belfast to Glasgow brought back memories of the Athenia; the black heaving swell, the hissing along the sides of the ship as she cut her way through the salt sea; but upper most in our minds were the scenes on the lower decks after the torpedo struck. It had left a claustrophobia from which I never recovered. Perhaps it had been there all along, but it made me realise that, if I were to play a part in the war, it couldn’t be in the confined space of a submarine, or even a ship, or a tank. It had to be the open freedom of the air. There is a basic difference in the make-up of a flyer and others. I’ve often heard submariners say the thought of being miles high in the sky in a small plane filled them with fear, and confided to them that most pilots would hate to face hours of inactivity, but grave danger, in a small submarine in the depths of the ocean.

So Katerina and I sat close together on the deserted deck, clinging together to keep warm in the cold, damp September night, both thinking of lurking U-boats and not daring to mention them, until the next morning when we sailed down the Clyde to Glasgow.

We were expecting to be greeted warmly by the Donaldson-Atlantic Line and learn when we could sail home. It was explained to us that the small print on our tickets explicitly stated that the Line’s responsibility to carry us across the Atlantic was null and void if ‘Acts of God or the King’s enemies’ prevented them from carrying them out. Since ‘the King’s enemies’ had sunk our ship, and since the others had been commandeered by His Majesty’s Government, there was nothing they could do for us at present, but they would let us know. In the meantime, we would be billeted in the Beresford Hotel. I at least got something out of it. I was presented with a badly cut, cheap suit and shirt. I accepted it gratefully. Somehow clothes didn’t seem to matter much in those days.

It was the next evening that Harry Lauder came. By now he was Sir Harry Lauder and almost seventy, but he was known to Scots, and almost everyone else around the world. He epitomized the tough, cocky little Scotsman, and brought a nostalgic memory of home, humour and sentiment to every corner of the globe, when, in a world with no air travel, ‘home’ was very far away, and would probably never be seen again. It was typical of him that he would come out of his retirement to give freely of his time to the Athenia survivors, and he gave of his best! From the moment the short stocky figure with his kilt and Glengarry bonnet, and his gnarled black stick arrived, he had us laughing and crying. All the old, well-loved jokes and songs came out one after the other: ‘Roamin’ in the gloamin’, ‘There is somebody waiting for me, in a wee cottage down by the sea’, ‘On the bonny, bonny banks o’ Loch Lomond’, and ending with the song he wrote himself, when his only son was killed in the First World War: ‘Keep right on to the End of the Road’. He left us all in tears, feeling a whole lot better!

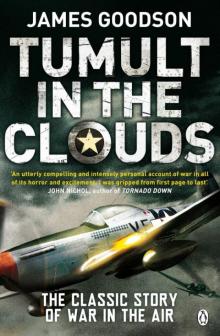

Tumult in the Clouds

Tumult in the Clouds