- Home

- James Goodson

Tumult in the Clouds Page 3

Tumult in the Clouds Read online

Page 3

The next day, walking down Sauchiehall Street, I saw three men in RAF uniforms putting the finishing touches on what was obviously going to be a recruiting station.

‘Can I join your RAF?’ I asked.

‘Come back tomorrow when the sergeant’s here.’

I was there at 9 a.m. At about ten the sergeant appeared, accompanied by two airman with their arms full of boxes of forms.

They had no shortage of volunteers, and a line soon formed behind me. Finally I was allowed in. The sergeant simply said, ‘Can you write? Then fill in this form.’

But I had lots of questions: ‘Can an American join the RAF? How long would I have to wait? …’

The sergeant sighed. ‘Look, son, the Air Marshal’s busy, so he’s just asked me to stand in for him. Just fill in the form, and don’t bother to apply for air crew.’

‘But why not? I want to be a fighter pilot.’

‘Of course you do, and so do a million others.’

‘But somebody’s got to be a fighter pilot, why not me?’

‘Just fill in the form!’

I filled in the form.

The next day I was back to see if they had any news. Suddenly, only one thing in life mattered: to become a fighter pilot as soon as possible. I took to hanging around the recruiting station. Sergeant McLeod and I became good friends, but this didn’t help my cause; on the contrary, I soon realised that, although the recruiting station religiously sent in their forms, it was a one-way street. They received no response from the Air Ministry, and it began to dawn on me how completely unprepared for war they were.

This was confirmed when Sergeant McLeod announced one day that an officer was going to turn up on a tour of inspection. I explained how essential it was for me to talk to him and McLeod promised to do his best.

Thus it was that I found myself in the presence of Flight Lieutenant Robinson. I was not only in awe of his rank, but also because he had actually served in the Royal Flying Corps at the end of the First World War. Talking to him made me feel that the war we were now starting was just a continuation of the last. He spoke of the Germans as ‘Jerry’, ‘the Boche’ or ‘the Hun’. Planes were ‘kites’, men were ‘types’: It was a language I was to become very familiar with. The US Air Force picked it up from the RAF, who had preserved it from the RFC of World War I. It’s not only in tactics and equipment that one war starts where the last leaves off. At least that applies to the victors. Only the vanquished seem to learn from the past, and prepare to take their revenge. And so it was that Germany was ready with a new concept of total war, based on air supremacy and perfect coordination between tactical air power and motorised infantry and armour, with the fleets of Me109’s, Me110’s, Stukas and Heinkels designed for the job. Meanwhile the Air Ministry contemplated the overwhelming problem of creating an air force to meet the threat, and processing my application form; and Flight Lieutenant Robinson expressed the pious hope that ‘Now that the balloon’s gone up, they’ll pull out their fingers and get cracking!’

He also gave me practical advice. ‘We can’t possibly train enough pilots in England. Even if Jerry would leave us in peace, the bloody weather would put the lid on it. No, the training’s going to take place in the Commonwealth, and mainly Canada. So even if the RAF get around to your application, and accept it, they’ve got to get you to Canada. On the other hand, the shipping Johnnies have to get you back to Canada. Now, if we can add to your application that you are going to Canada under your own steam, that should help. At least, your case would stand out from the mass. There might even be a good piece of publicity: young American torpedoed on the Athenia volunteers for the RAF.’

I appreciated what he said, but I was sceptical about the liaison between the RAF in England and the RCAF in Canada.

‘That’s fine’, I said, ‘but when I turn up in Canada, they may not have any record of my application here. I wonder if I could ask you to write a letter confirming that I have volunteered here.’

‘Jolly good! ’ He was so willing, I decided to risk all.

‘Perhaps you could suggest that they consider my application favourably?’

‘Oh, I don’t think I could commit the RAF to that!’

‘It would simply be your personal opinion.’

‘Yes! Why not. Jolly good show!’

I never knew if the letter helped, but it may well have done. In those days especially, lives were changed, and lives were lost, by even more insignificant happenstances.

In one respect, Robinson was right. After an initial reaction of non-committal pessimism, the Donaldson Line and the Admiralty were paying more attention to us. We were treated to bus trips to Loch Lomond, and were well looked after in our hotels. What’s more, we were told, for the first time, that arrangements were being made to give us passage back to Canada. More important, they had given us some pocket money, which, together with a loan from my aunt, gave me enough for a trip to London. Along with the rest of the population, we had been issued with gas-masks. It was carried over the shoulder in a cardboard box, and this, with a tooth-brush, tooth-paste and a bar of soap, tucked into it, was my luggage. The almost immediate supply of gas-masks to the entire population of Britain was to me one of the many enigmas of that strange period, and one which has never been commented on. Against a background of general complacency and complete unpreparedness, the Government somehow produced some fifty million gas-masks almost overnight!

London in those first few days of World War II was in an unreal sort of daze. The war in Poland was drawing to its inevitable tragic end; but Poland was far away, and most people thought that when Germany came up against the combined might of England and France, we would be ‘hanging up our washing on the Siegfried Line’. But behind the stoic good humour and jingoism, there was uneasiness and fear, and business was not quite as usual as they tried to make out.

The theatres were still putting a brave face on it, in spite of the black-out, but it was a losing battle. John Gielgud, Edith Evans, Peggy Ashcroft and Margaret Rutherford were playing in Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of being Earnest at the Globe theatre, and I spent my last resources on what I thought would be a chance I might never have again. In the theatre, I admired the ornate, gilded cherubs and Edwardian decorations, but the large theatre was practically empty. Scattered through the empty seats was a handful of people; but the cast gave a brilliant, polished performance. I suppose Gielgud was in his late thirties at that time, tall, thin and elegant. He was so perfect in the leading role that it was impossible to imagine it being played by anyone else. He belonged in the precious, prim, well-ordered world of Victorian England, as did Edith Evans as Lady Bracknell, and all the rest of the cast. The play ended with polite curtain calls, and ‘God Save the King’.

We went out into the blacked-out, bewildered, frightened world of pending doom and horror. Not for the last time, I felt that most of the English were as unprepared for it as John Worthing, Dr Chasuble, Miss Prism and Lady Bracknell.

Back in Liverpool, the liner, The Duchess of Athol, was preparing to sail for Montreal, carrying, in third class, those refugees from Eastern Europe lucky enough to have scraped together enough money to allow them to leave behind the grimness of Europe at war to start a new life in the new world. In second and third class were the remaining Canadian and American tourists, who had delayed their departure too long. There were also British officers and training personnel, the first of the many who would work with the Canadians in the formation of, and training of, the Air Force under the Commonwealth Air Training Scheme. Somehow, the Admiralty also found room for the Athenia survivors.

Soon, once again we were sailing down the Mersey; once again waving goodbye to the Liver birds perched on top of the Liver Building, passing Birkenhead, New Brighton, Wallasey and Bootle, and then out to the open sea.

The ship lived up to her reputation for rolling, which had earned her the nickname of The Drunken Duchess.

We sailed alone, zig-zagging, and blacked-ou

t at night. The theory was that the speed of the large liners, combined with constant changes in course, would give them a better chance against the slower U-boats than if they were part of a convoy where they would be held down to the speed of the slowest freighter.

It seemed to work. In a week, we were sailing down the broad St Lawrence, looking out at the brilliant scarlets, yellows and browns of the trees in the late autumn in a bright new world.

CHAPTER TWO

The Pole

Finally, I found myself in one of the vast halls of the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto. This whole complex had been turned over to the Royal Canadian Air Force as the only accommodation large enough to process the thousands of airmen involved in the Commonwealth Air Training Scheme. We would be herded into one of the exhibition halls, clutching our process documents, and be called out for the next stage.

‘All those who have had their interview, had their medical, but not their dental inspection, follow me.’ And a mass of humanity would surge forward. It was the start of a system of classification and elimination which continued throughout the whole training period, until the chosen élite emerged as fighter pilot candidates. The slightly less fortunate became bomber pilots, or observers, or were obliged to become ground crew. The greatest catastrophe, and a terrible fear that dominated a would-be airman’s entire training career, was the constant threat of being ‘washed-out’. Out of those thousands of eager young airmen, probably less than five percent would become fighter pilots, and of them, far less than one percent would ever score a victory.

In that crowd of uniform humanity, one figure stood out. Taller than the others, with a thin handsome face, he had a strong, sober dignity, which distinguished him from the nervous, jabbering youngsters around him. His good looks were enhanced by a scar on the side of his aquiline nose, which also gave him a slightly disdainful look. He would have been ideal in a Basil Rathbone part in a Shakespearian tragedy. This was the first time I set eyes on Mike Sobanski. It was on the medical parade that I got talking to him. He was having trouble understanding what was being said to him. I thought he was probably French-Canadian, and offered to help; but his French was far from perfect, so I tried German. This went much better, and, after the medical, we stayed together and chatted. I learned that he and I were probably the only ones in all those thousands of enthusiastic youngsters who had any taste of war. While I was splashing around in the bowels of the stricken Athenia, Mike was crouching in the rubble of Warsaw, as the German bombers pounded the dying city.

He had been a university student, and had tried to join the Polish Air Force when the Germans attacked; but it was too late for the Air Force to take on young men for training. They knew the war would either be won or lost long before a long training course could be completed. In any case, their shortage was in planes, rather than in pilots.

So Mike found himself, a private soldier in the infantry, inadequately trained, riding a train to the Vistula River to reinforce a battle front which, like the whole of Poland, was crumbling before a German army, and a German air force, which blasted everything that stood in the army’s way, and destroyed the vitals of the whole country. Even the train carrying Mike and the rest of the last desperate, hopeless young recruits came under attack from the Stukas. They didn’t even need the protection of the Me109’s. They had already done their job of annihilating the Polish Air Force, much of it on the ground. Even in the air, the slow, obsolete high-winged PZL fighter planes would have been no match for the 109’s, even if they had not been hopelessly out-numbered. The Italian General Douet had said in 1921, ‘A decision in the air must precede a decision on the ground,’ and General Billy Mitchell had preached the theory of subjugating an enemy by air attack. If other nations only paid lip service to the idea, the Germans had learned the lesson, and learned it well. Kalinowski, then a major in the Polish Air Force, and later a wing commander in the RAF, put the number of operational planes in the Polish Air Force at the time of the German invasion at 150 fighters and about the same number of bombers. Against these, the Germans threw in about 1,500 modern front line aircraft, backed up by at least the same number in reserve in Germany. Colonel Litynski wrote: ‘Already by the second day the telephone and teleprinter systems had broken down … As a result, there was virtually no effective military command from the start.’

Mike Sobanski was becoming increasingly aware of the inequality of the battle. The train crawling towards the crumbling front was as helpless as a worm about to be pounced on by a bird. At 5,000 feet above, the Stuka pilots went through the drill which was now so familiar to them: ‘Close radiator flap. Turn off super-charger. Tip over to port. Set angle of dive to 70 degrees. Accelerate to 300 mph. Apply air brakes. (which also caused the high-pitched wail, a fore-warning of the destruction to come to the terrified victims). Take aim on the target. At 3,500 feet, press the release button on the control column.’

With the same deadly accuracy which had paved the way for the advance of the panzers across Poland, the bombs blasted the railway tracks, and the train itself.

Mike heard the dull drone of the planes turn into the rising roar of the engines in the dive, and then the banshee scream of the air brakes. There was a sudden flash of flame and wind like a body blow, as the bombs exploded.

Mike came to, numbed and confused, coughing blood and dust out of his throat as rescuers tried to free him from the debris. The shattered glass had lacerated his face and slashed through his nose. His legs were pinned by something heavy; bombs were still falling; and there was nothing Mike or anyone else could do about it. The feeling of helplessness gave way to angry frustration. Then a furious, determined rage took over; a hatred for the grinning, wailing Stukas, smashing Polish trains, troops and men, women and children; a hatred for the efficient panzers riding down the Polish cavalry; a hatred for the self-confident Germans, making a graveyard out of Poland.

And out of the hatred, came a solemn vow; a vow never again to lie helpless in the rubble and dirt; a vow to be up there in the free air, in the driver’s seat, looking down on the pathetic ants on the ground, calling the shots, holding the power – like a god!

Mike lay in hospital in Warsaw while his country was being destroyed. On 17th September the remaining serviceable Polish Air Force planes flew out to Rumania to surrender before they too ran out of spares. The pilots made their way to France, and then to England, where they formed the Polish squadrons in the RAF, which became the highest scorers in the Battle of Britain. On 25th September a massive unopposed Luftwaffe air raid on Warsaw forced the final capitulation.

That night, Mike crept out of his hospital bed. He found that he could only hobble on one good leg, but he knew this was the time to move. They didn’t know he could walk, and, in the general confusion, he made his painful way out of the rear of the hospital. Near the back exit, there was a row of hooks where the porters and male nurses left their coats. Mike found one that he could get into, even if it was short, and limped out into the smoking, defeated city. German military vehicles and marching infantry were everywhere, but they were too busy to pay attention to the huddled, crippled creature hobbling through the debris.

He was making for the family house. There, perhaps, there would be some news of his mother and father, if only from the neighbours. His father was a colonel in the infantry. He’d had no news from any of the family or friends for two weeks.

He had hoped that the area, being residential, would have escaped the bombing, but, as he turned into his street, his ideals of chivalry took another knock. In the determination to shock the population and Government into capitulation, the bombing had been indiscriminate. His street was no different from the others he had dragged himself through: burning buildings, pathetic piles of personal belongings, rescued from the rubble; dazed and bewildered people moving aimlessly among the chaos; a few firemen trying to cope with rescue work; a few ambulance men caring for the wounded. It was a scene which was to become hideously familiar across Europe.

It was the start of a virulent plague which would spread to almost every city and town, leaving death and destruction: destruction of a whole era.

Mike found himself staring dumbly at the ruined house. Some of the walls were standing, but it had been gutted by fire. Slowly he stumbled into the rubble, not knowing what he was looking for, nor why. Lying shattered on the floor, was the grand piano on which his mother had accompanied herself as she sang so beautifully one glorious operatic aria after another in those unbelievable, idyllic days a month – a million years ago. It was all dead now, like the smashed, yellowing photographs of old family grandparents still in their silver frames, or the broken porcelain in the broken cabinet, which had been his mother’s love and pride, or the scattered toys, which she had treasured because he had treasured them.

Then he became aware of the approaching figure. The straight back was now slumped, and the eagle eye was dimmed, but Mike knew him almost before he saw him.

‘Father!’

Mike took him in his arms, as his father had taken him so often as a child. They stayed in each other’s arms, not wanting to show their tears. Finally, Mike asked the questions he hadn’t dared to ask.

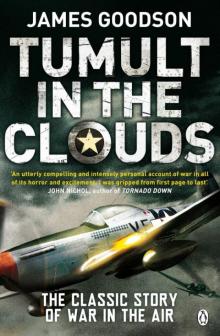

Tumult in the Clouds

Tumult in the Clouds